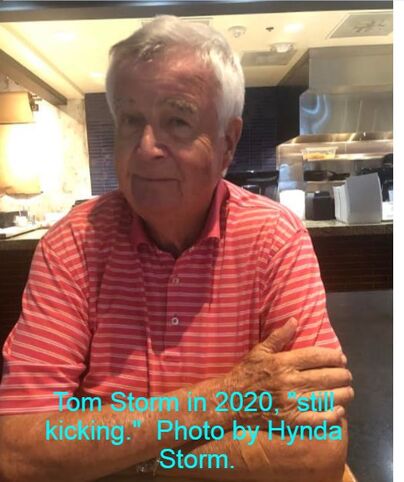

The former President of Trench Mfg. Co. recently spoke with Pennant Fever about his days leading the biggest pennant maker of the 20th century.By K.R. BiebesheimerFor more than three decades, Thomas W. Storm ran Trench Manufacturing Co. in Buffalo, NY. During his reign the company grew into the nation’s largest and most innovative maker of pennants. In 1995, however, the company had to close its doors after 75 years in the business.  Trench’s company history has only recently come to light, thanks in part to BLOGs like this. But even this writer was stumped to find much of anything on the former President, Director, and Chairman of the company. In all my hours researching Trench, all I learned of Thomas Storm was: (a) he graduated from Princeton in 1955; (b) he and his brother John Storm ran the company together for several decades; and (c) he once lived in a beautiful Tudor home on Bradenham Place in Buffalo. In fact, when I first wrote about Trench in 2018, I wasn’t even sure Tom Storm was still living. Then one day I got an email that abruptly opened: “I'm still ‘kicking’ and would be glad to talk to you about my years in Trench.” It was signed, “Tom Storm.” Apparently, Mr. Storm’s family found my BLOG; alerted him of it; then brokered our introduction. Last month Mr. Storm graciously spoke with me for 90 minutes via telephone from his home near Boca Raton in Florida. Here’s the highlights of our conversation: A family affair Storm’s connection with Trench actually came via his father, Robert Storm. It was his father that purchased the business from George A. Trench, the company’s founder. Upon graduating from Princeton University in 1955, Storm began working for Dow Chemical. He had no plan to own a business; let alone, run a felt novelty company. That all changed in 1958 when his father purchased a controlling interest in the Buffalo-based pennant maker. After nearly 40 years in the pennant business, George Trench was ready to retire. When Storm’s father learned that George’s share in the company was for sale, he bought it. Storm had no idea what prompted his father to make the purchase; but, from thereafter, the Storm family was in the pennant business. A few years later Franklin T. Richards sold his minority stake in the company to the Storms, giving the family a 100% interest. In 1961, Tom left Dow Chemical and began working full-time at Trench. Prior to that point, the company had been run by two key employees: Irene Morin, who ran the internal operations (production); and Hank Morin, who handled exterior matters (sales).

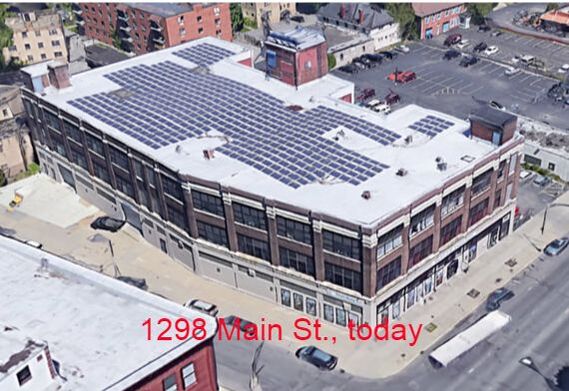

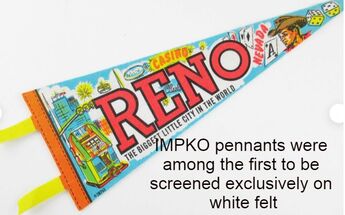

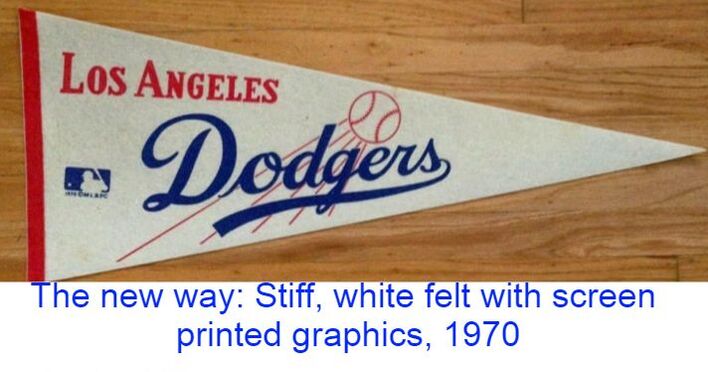

Storm quickly found new real estate across the street at 1298 Main Street. In these new digs, Trench enjoyed unfettered elevator access to 25,000 square feet on the third floor of the spacious building. The move was timely. Storm had an ambitious set of plans for the company and he would need every square foot of real estate to bring that vision to life. Modernization With his new real estate secured, Storm sought to modernize the entire production line at Trench. When he arrived in 1961 the company was doing okay financially; but it wasn’t thriving. Initially, he had serious concerns over their pennant production line, which he described as “antiquated.” By the 1960s Trench was still making felt pennants the same way they (and others) had since the 1920s. Every step was labor intensive. Storm described the process in excruciating detail. First, you had to carry 10-15 different colors of felt on hand for the customer to choose from. The felt was an inexpensive blend of only 30% wool. Next, the designs were screen printed in one color: white. After screening the graphics, the felt was left to dry on a drying rack overnight. The next day an employee had to apply the secondary colors to the design via an airbrush. Because the paint was toxic, the air brushing room had to be walled off from others and be well ventilated. Once airbrushed, the pennants were again set out to dry. After a year's time, you could count on these secondary colors fading. Finally, the spine and tassels had to be sewn on by a seamstress. When complete, each pennant was sold to a concessionaire, distributor, or retailer for a mere $0.25/pennant. “It was a good business; but it wasn’t a multi-million dollar business,” Storm claimed. The extensive production costs outlined above ate it into their profit margins considerably.

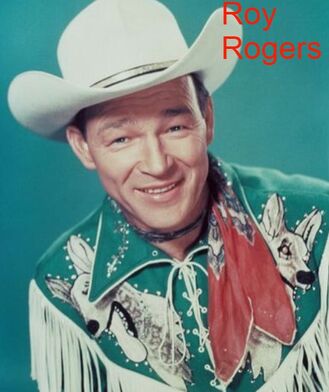

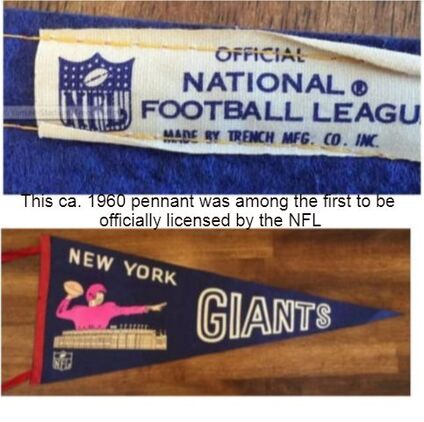

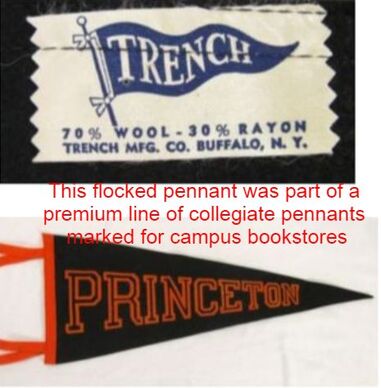

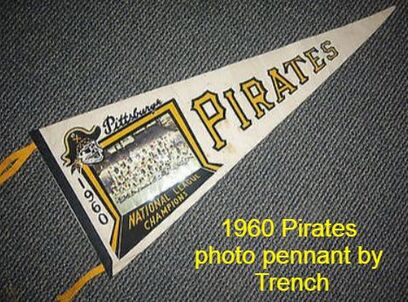

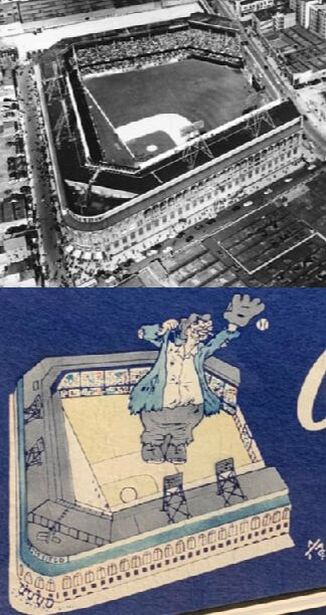

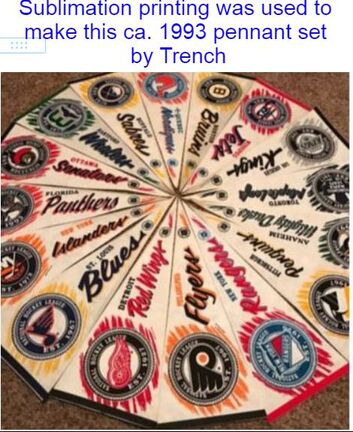

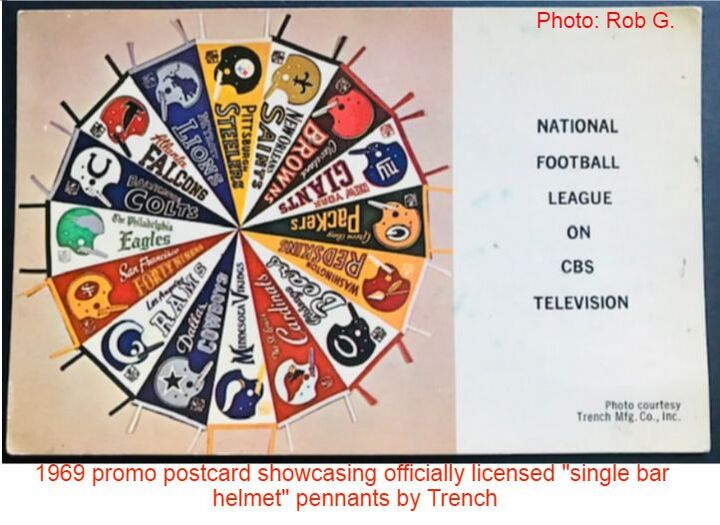

See the difference for yourself in these two Trench pennants from that transitional era.... But Storm’s modernization would not stop at white felt. Screen printing, even on a white felt substrate, remained too labor intensive for his liking. So, by the 1980s, he converted their production line from screen printing to sublimation printing. Now, using a stiff, synthetic, white felt, Trench could mass produce pennants on an industrial strength sublimation printer. No more screening. No more airbrushing. No more drying racks. From a business perspective, this was the only way to make a pennant.  Licensing Trench’s production methods were not the only thing to change when the Storms acquired the business. In 1959, a year after Storm’s father purchased the company, the NFL became the first pro league to begin licensing their intellectual property (IP). In those early days, the NFL had no experience with licensing. So the league turned to the one guy that did: Roy Rogers. Yup, that Roy Rogers. The celebrity cowboy; and successful businessman. [Up until 1959, none of the pro leagues protected their teams’ IP. Roy Rogers was the first celebrity to cash-in on his name, licensing it as a brand name to other manufacturers for use on cowboy-themed merchandise that his fan base gobbled up. In fact, Roy Rogers Enterprises, as his licensing company was called, was so successful, Rogers made more money licensing his name to other makers than he ever did making films. By the decade’s end, Pete Rozelle and the NFL looked to the cowboy-turned-businessman for help licensing their IP. Then in 1962, the league started its own licensing division, now known as NFL Properties.]  The Roy Rogers-NFL partnership ended up being a very good thing for Trench. In those days, Trench’s biggest customer was Sportservice, the Buffalo-based concessionaire responsible for ballpark concession stands across the country. Sportservice’s principal buyer was Ed Martin. When Martin got wind of the NFL’s desire to begin licensing their IP through Roy Rogers Enterprises, Martin advised Storm’s father. Thanks to Martin’s tip, Trench was able to secure an exclusive license to make NFL pennants beginning in 1960. In the following years, Trench would secure other licenses to make pennants from the AFL, MLB, NHL, and the NBA. Experimentation By 1961, Trench was the nation’s largest maker of felt pennants. They dominated the professional sports market and would continue to do so thanks to the licenses they secured from the big four pro leagues. Naturally, they looked elsewhere for new markets to conquer; and they set their sights on the collegiate market. [Up to that point the collegiate pennant market had been dominated by two companies: Collegiate Mfg. Co. of Ames, IA; and Chicago Pennant Co., of Chicago, IL. The collegiate pennant market worked a bit different from the pro sport and souvenir pennant markets. Collegiate pennants produced by these two companies were generally premium items. For example, these two makers screen printed flocked graphics on all of their pennants. This production method yielded rich, colorful graphics that were velvety smooth to the touch. Because it cost more to make pennants this way, these items were principally sold in university bookstores, were patrons could take the time to examine their quality workmanship for themselves.]  Trench’s foray into the collegiate market would not last long. To compete with the premium pennants already on the market, Trench began making flocked pennants of their own in the 1970s. This premium line was further distinguished by the presence of a handsomely designed sewn label on its reverse. Storm recalled the manufacturing process being even more troublesome than the traditional screen printing method. They quickly abandoned the effort, opting to make collegiate pennants the normal way: with screen printer's ink and a squeegee. Concessionaires By the time Storm joined Trench in 1961, the company’s most significant client was Sportservice, the aforementioned concessionaire conveniently located down the street. This relationship had been pioneered by George Trench decades earlier. As new concessionaires entered the market, Trench cozied up with them, too. By decade’s end Trench was supplying pennants to ARA Services, Canteen Corp., Harry M. Stevens, and other concessionaires managing ballpark merchandising across the country.  Storm stressed the importance of concessionaires in a business like his. Trench didn’t sell pennants directly to sports teams, national parks, museums, etc. Rather, they sold to the concessionaires that ran these venues. The Los Angeles Dodgers and the Oakland Athletics were the exception, as these two teams managed their own concessions within their ballparks. “Danny Goodman ran concessions for the Dodgers,” Storm recalled, “and he loved Trench. He was a great customer for us.” Distinctive products Although Storm has been out of the pennant business for decades, he remembers everything about the pennants his company once made. Especially the production details--and the headaches that came with certain styles offered.  The Photo Pennant they developed was not, in fact, Trench’s idea. Rather, it was Sportservice’s Ed Martin’s suggestion. Martin predicted that these would be big sellers. He was right. Unlike other pennant styles offered, Trench’s photo pennants were exclusively sold inside ballparks. They offered them well into the 1970s. “These were a big pain in the ass,” Storm advised. He then explained the additional steps it took to make a photo pennant: first you had to go to a printer and print 10,000 photos up; then you had to die-cut a rectangular hole in the head of the pennant for the photo window; and then someone had to affix the photo to the pennant. The Date Pennant was another fan favorite. But not for Storm. “Nobody else was crazy enough to make these,” he said with amusement. As with the photo pennant, the decorative sash this style came with added to its production costs; which of course ate into Trench’s profit margins. Not only did they have to make the sash; they had to slot it through the head of the pennant, which had to be done by hand. Unlike the Photo Pennant, Date Pennants had been offered by Trench for many decades. Much to Storm’s chagrin, this style remained popular with souvenir retailers because the pennant always looked fresh. “We even swapped-out the old sashes from retailers’ unsold stock for new ones with the current year on it,” Storm added. Pennant artwork When Storm joined Trench in 1961 their art department consisted of two graphic artists. As the company expanded into new markets and product lines, more artists were added. Perhaps the finest example of their artwork concerned another popular product line: the Stadium Pennant. Today, collectors of vintage pennants value these pennants because of their original artwork. That’s because Trench’s artists made an accurate rendering of seemingly every team’s ballpark; then they incorporated it into the graphic designs of that team’s pennants. These pennants stood out from those of their competition, many of which relied on generic images of players and ballparks in lieu of original drawings.  Storm agreed that all of their stadium pennants appeared to have been developed by the same artist. Unfortunately, he could not recall that artist’s name. But, in terms of talent, he had no difficulty downplaying the extent of their skills. Storm simplified his own art department’s work as such: they took a picture of a ballpark and they traced it. “There was no van Gogh or creativity involved--just tracing.” Perhaps that's selling their talents a bit short? Nevertheless, there may be some truth to this explanation, as evidenced by this ca. 1955 aerial photo of Ebbets Field--which likely served as the inspiration for Trench's rendering thereof, below it. Storm further added: Trench never bothered copyrighting their pennant artwork. This was interesting. Throughout the 20th century, many pennant makers engaged in the industry-wide practice of reproducing (stealing?) the artwork of their competitors for use on their own pennants. Storm was hardly bothered by this. “Anything we did they could do what they wanted with,” he replied with little emotion. Final thoughts After 90 minutes talking pennants with Storm, two things became evident. First, he doesn’t quite appreciate the significance of his company today, a quarter of a century after it closed. At least, not like I do. “We were in the pennant business. We weren’t Bethlehem Steel!” he quipped. Second, what he values in a pennant is not necessarily what you or I value. Collectors of vintage pennants tend to appreciate the craftsmanship that went into making them: the materials used; the sewing performed; and of course, the artwork. But Storm isn’t a pennant collector. In fact, he doesn’t own a single pennant today. Although he does display a Princeton felt banner in his Florida home ... it wasn’t even made by Trench!  Rather, Storm was the head of a company. He ran a for-profit business that at one point employed hundreds of people. Ultimately, his job was to ensure that Trench Mfg. Co. remained profitable. If that meant selling lower quality pennants made on a sublimation printer, so be it. If that meant focusing on sportswear over pennants, why not? For Storm, a good pennant was one that he could make money on. In the 1960s, that pennant looked like something we collectors value today. By the 1980s, however, it looked drastically different. Consumer interests of the day had changed, necessitating the production of cheaper pennants. Storm recognized this. He had to. These were business decisions, and he was a businessman after all. Not a pennant collector.  With all business comes risk; and even well run companies run the risk of failure. In 1995 Trench was forced to close its doors after 75 years in the pennant business. “We had a good run,” he lamented, “but like Eastman Kodak … it all came to an end.” He pointed out that many of the other pennant makers from the previous century were similarly forced out of the business decades earlier. Storm’s been retired for 25 years now. At age 87, he’s still sharp as a tack. He plays golf everyday. He probably doesn’t miss those Buffalo winters. Looking back on the company he and his family grew together, he remarked: “I still can’t believe my dad bought that company … but I’m sure glad he did. We had a lot of fun.” For more on Trench Mfg. Co., click here. For more information on the NFL-Roy Rogers partnership, click here. Note: All unquoted material on these pages is © 2020 K.R. Biebesheimer & Son. All rights reserved. Short excerpts may be used after written permission obtained and proper credit is given. ♦♦

5 Comments

|

About me...I collect vintage pennants and banners. Soon after getting into this hobby, I became curious about the companies responsible for their production. I had to look hard, but eventually found a lot of interesting information on many of them, and their products. This site is my repository for that research. Periodically, I will dedicate a post to one of these featured manufacturers. I hope other collectors will find this information useful. Featured Content:

All

Archives

November 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed